Does Australia have a current account surplus? (Yes -- and it's kind of a big deal)

The quick version:

Australia has a current account surplus (CAS)

This is the first time Australia has recorded a CAS since the late 1970s

Australia’s CAS is caused by its Balance on Goods and Services surplus. The Net Primary Income balance is still in deficit.

Australia has a current account surplus. This is important

When I studied Economics at high school we never talked about a current account surplus (the CAS). Australia simply didn’t record a CAS. Instead, Australia was known for its current account deficits (CAD).

Things have changed in 2022. Australia has had a CAS for a period of time and it’s an economic statistic that signals some important things about the Australian economy.

Let’s rewind a little.

My HSC Economics exam and writing about a current account deficit

When I sat my HSC Economics exam, we only ever wrote about Australia having a current account deficit. We NEVER talked about current account surpluses.

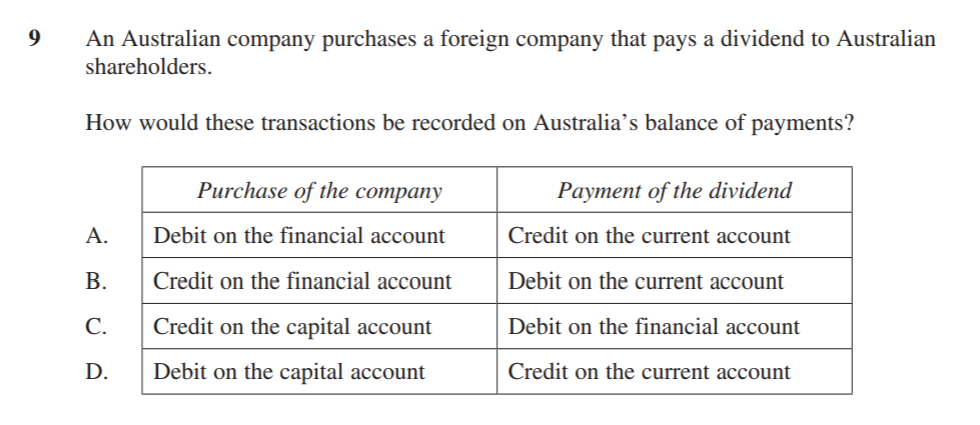

Have a look at this stimulus for one of the essay questions.

Source: NESA

You can see that the current account balance for 1997/98 was a deficit for $23 billion. Let’s fast forward to now.

In the September quarter of 2021, Australia recorded a CAS of nearly $22 billion.

This CAS shrank to around $13 billion in the December quarter. But Australia still has a current account surplus.

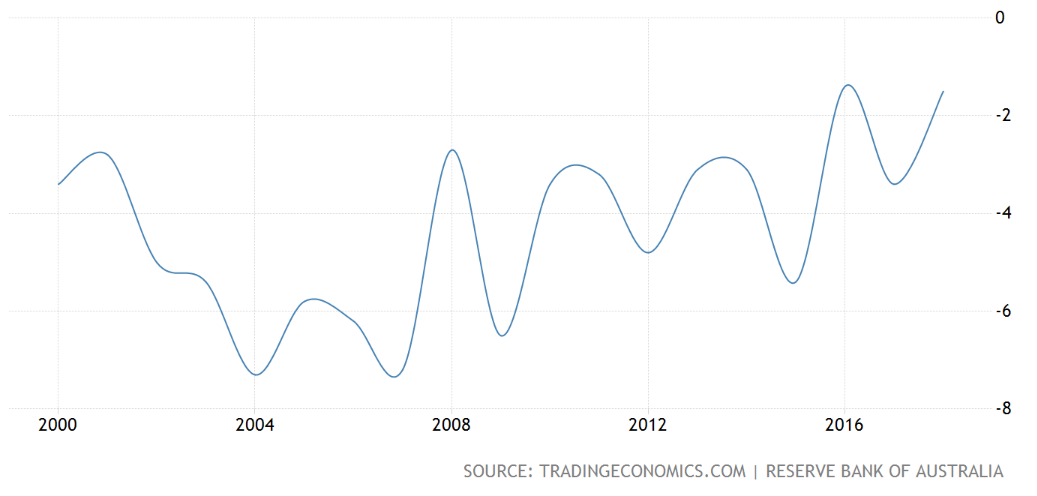

On a personal note, I never thought Australia would have a CAS. Why would I? Have a look at this graph below. For my lifetime (up until now), Australia has had a persistent CAD.

The numbers on the right hand side of the graph represent the size of the current account balance as a percentage of GDP. So the larger the % of GDP, the larger the size of the CAD. You can see that in the mid-2000s the CAD was over 7% of GDP – a very large amount.

Why does Australia have a current account surplus in 2022?

The key drivers of Australia’s CA balance are:

The Balance on Goods and Services (BoGS)

The Net Primary Income (NPY) balance

As the value of BoGS and NPY change, so does the balance on the current account. Typically, Australia’s BoGS fluctuates considerably – due to the frequent changes in the prices and volumes of our exports. For example, the price of iron ore rarely stays the same. It’s not like manufactured goods that have relatively consistent prices. An iPhone’s price doesn’t fluctuate from day to day.

Australia has a persistent NPY deficit. This hasn’t changed.

So why has the CA has moved into surplus? Because of Australia’s BoGS surplus.

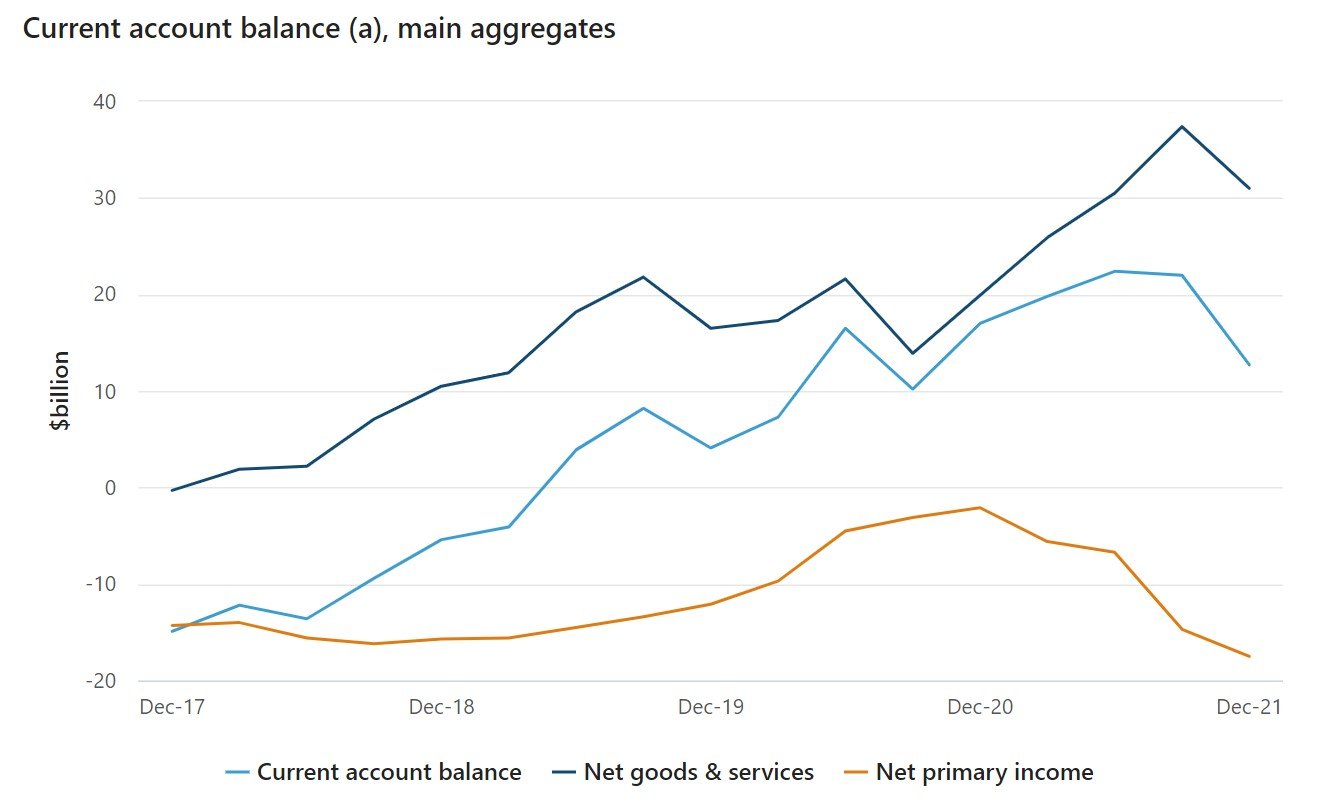

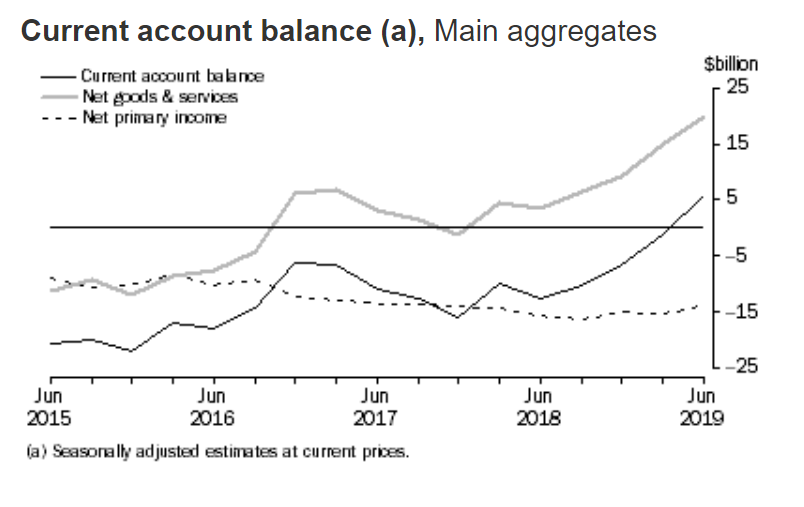

Have a look at this graph.

You can see that BoGS – the dark blue line – is leading the CA balance higher into surplus.

NPY is actually getting larger – the deficit is growing. This is pushing the CA balance the other way — so reducing the size of the surplus.

So the driver of the current CA surplus is the BoGS surplus. You can also call BoGS the trade balance or net exports.

Australia’s BoGS surplus is caused by an increase in Australia’s export sales (particularly of natural resources) and a slowdown in import spending (due to the impact of the pandemic).

What are the consequences of Australia’s CAS?

Here are some of the consequences of Australia’s CAS.

As Australia is selling more exports, there is greater demand for labour/resources into the export sector. This is to meet the growing demand for overseas markets.

Australia may also require greater investment in the mining sector to help increase the volume of natural resources that can be obtained and sold overseas. This could increase capital inflows in the form of loans from overseas. This, in turn, will increase income outflows and then increase the value of the NPY deficit.

In addition, as exports will be growing, they will contribute more to Australia’s aggregate demand. This is because AD = C+I+G+(X-M). So, as exports volumes rise, they will positively influence net exports (X-M), which will add positively to AD and the nation’s economic growth.

Not a lot of people are talking about the CAS. But they should be. It’s a very important statistic with important consequences for the Australian economy.

Want more on why Australia has a current account surplus?

I also have this video that looks at the drivers of a CAS (see below). It could be very helpful in trying to grasp this potentially tricky concept. A concept I never thought I’d see in my life.