This is an extraordinary development. Despite oil shocks, debt crises (Latin America and Greece), the Asian Financial Crisis and various wars, the global economy has kept growing.

But in late 2019, economists have been vocal about potential risks to global economic growth.

A synchronised slowdown

In mid-October 2019, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) downgraded (reduced) its forecasts for global growth. The IMF forecasts that global growth to fall to its weakest pace since the GFC.

Just look at the language the IMF used:

“The global economy is in a synchronised slowdown and we are, once again, downgrading growth for 2019 to 3 per cent, its slowest pace since the global financial crisis. Growth continues to be weakened by rising trade barriers and increasing geopolitical tensions.”

In terms of figures, the IMF forecasts that the world’s advanced economies will grow by 1.7 per cent in 2019 (compared to 2.3 per cent in 2018). Growth in emerging and developing markets has also been downgraded to 3.9 per cent in 2019 (from 4.5 per cent in 2018).

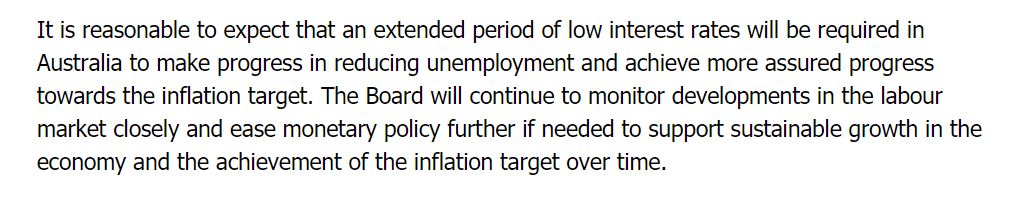

Monetary policy might be working

There has been some debate about the effectiveness of monetary policy (central banks’ use of official interest rates to boost economic growth) in economies around the world. But the IMF says the use of MP has been very helpful.

According to the IMF, if governments around the world had not loosened monetary policy (reduced official interest rates), global growth would currently be 0.5 percentage points lower in 2019 and 2020.

So, what happens next?

The IMF would like to see governments to do more to improve the state of the global economy. This includes removing trade barriers and ending the trade war, and implementing expansionary fiscal policy, particularly involving additional investment in infrastructure. In Australia, the Reserve Bank of Australia has been arguing for the latter.

The IMF is clear: now is the time to act. “The global outlook remains precarious with a synchronized slowdown and uncertain recovery. At 3 per cent growth, there is no room for policy mistakes and an urgent need for policymakers to support growth,” the organisation says.

We’ll have to see how the governments respond.