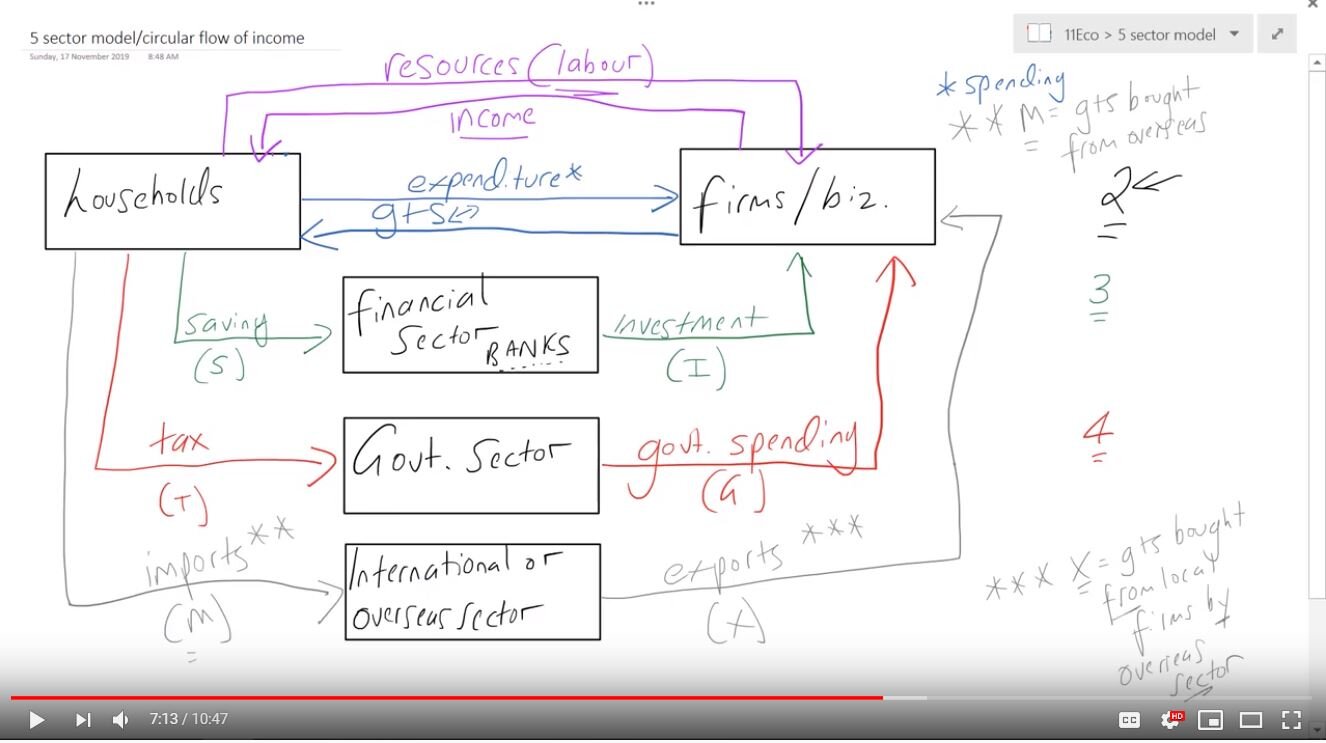

Step one: The two sector model

In this model, we just have households and firms. We have simplified the economy enormously!

Households supply firms with resources (such as labour). Then, firms supply households with wages in exchange for their labour.

Another flow is that households purchase goods and services produced by firms. So firms provide households with goods and services, and households buy these goods and services (known as consumption).

Step two: The three sector model

We now add the financial sector.

Households deposit their savings with the financial sector. The financial sector then lends these savings to firms to help them grow and expand (this is known as investment).

Step three: The four sector model

We now include the government into our simplified model of the economy.

Governments collect taxes from households (so, households pay tax to the government). The government then spends money in the economy in many ways, including unemployment benefits and infrastructure spending. As a whole, this is called government spending.

Step four: The five sector model

Now, we include other economies (from other countries). This is called the international or overseas sector.

Let’s say we’re talking about the Australian economy. Households buy goods and services from overseas. These are called imports and involve money leaving Australia. Then, Australian firms sell goods and services overseas. These are called exports and involve money flowing into Australia.

A little extra

When we talk about the five sector model, we discuss money flowing into the economy (injections) and money leaving the economy (leakages). I discuss this in detail in the video below, but here’s a summary table that can help. You can also read on about the five sector model and variables such as economic growth, unemployment and inflation.